Vestments

and

Liturgies

A plea for a more general use of the historic Vestments

and Liturgies of our Church

By J. A. O. STUB, D. D.

PASTOR

CENTRAL LUTHERAN CHURCH

[Minneapolis, Minnesota]

A plea for a more general use of

the historic Vestments and

Liturgies of our

Church

|

A |

SHORT time ago the announcement was made, that hereafter the Minnesota Supreme Court would appear in judicial robes, when sitting as a court. This decision was made at the request of the Minnesota Bar Association. At least one of our great metropolitan dailies commended the decision.

Now, this article is not primarily a plea for the robing of our clergy. We all agree that this question allows of different answers. It is, however, an effort to encourage more uniformity in our vestments and liturgies.

As a boy I always looked forward to the “Communion services.” My childish ear grew easily wearied with the sometimes lengthy Sunday services. But, the Holy Communion, as observed in the churches I attended, held a ‘Special appeal for my childish imagination. There was always something that appealed to the eye. And, is not the eye an infinitely finer organ of sense than the ear? It has often seemed that the services in modern Protestant churches have made their appeal almost solely to the ear.

My sainted grandfather, Jacob Aall Ottesen, always celebrated the Communion, robed in the colorful, and, as it seemed to me, beautiful, vestments of the Lutheran Church. On ordinary Sundays he wore the narrow-sleeved cassock, with its long satin stole, and the white “ruff,” or collar. But on “Communion days” and on all festival days he also wore the white surplice or cotta. As he stood reverentially before the Altar with its lighted candles and gleaming silver, the old deacon, or verger, placed over his shoulders the scarlet, gold-embroidered, silk chasuble. This ancient Communion vestment was shaped somewhat like a shield. As it was double, one side covered his back and the other his chest. Upon the side, which faced the congregation when he turned to the Altar, was a large cross in gold embroidery; upon the other was a chalice of similar materials. As a child I instinctly knew that the most sacred of all observances of the Church was about to be witnessed. As grandfather turned to the Altar and intoned the Lord’s Prayer and the words of consecration, with the elevation of the host and the chalice, I felt as if God was near. The congregation standing reverentially about those kneeling before the Altar, made me think of Him who, though unseen, was in our midst. I forgot the old, cold church with its bare walls, its home-made pews and its plain glass windows. I early came to know some words of that service, such as: “This is the true body, the true blood of Christ”; “Forgiveness of sins”; “Eternal life.” I venture that all who, like me, early received such impressions of the Lord’s Supper, will approach the Altar or the Communion with a reverence that time will but slowly efface.

Communion in a Danish village church. The fathers of our Church were thus robed.

There was a time, and not so long ago, when only infrequently was the glorious symbol of Christ’s victory, i. e., the plain cross, permitted upon our churches and Altars. Today, we can seldom know from the outward appearance of the newer church buildings whether they have been erected by Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Episcopalians, or Methodists. At least outwardly the cross is elevated for the gaze of the often tired souls that pass our churches. A little booklet recently to hand from the Methodist Board of Home Missions, recommends in every case, the erection of Gothic structures, with Altar and pulpit, and in every case a crucifix upon the Altar. Yes, there is even a Communion rail fronting the chancel. A Lutheran congregation would feel quite at home, and would find the building its chancel and Altar entirely in keeping with its own usage and traditions.

Many of us have made somewhat similar observances as to robes, or vestments, for the minister. A prominent Methodist divine, who worshipped with my people, attending three of our Sunday meetings, told me that the use of robes occasioned no particular notice among Methodists any more. His conference, he said, was about ready to begin using robes.

The day is past, when it is considered “Catholic” to have a cross on the highest point of the church building and upon the Altar. The same is true as regards organs, Altars, stained-glass windows, crucifixes, and candles in our churches. Why, one of the great new hotels of our country features a beautiful prayer chapel, open to all. Nor is it considered “Romanizing” for the minister and deacons to be robed.

(In Severinsen’s book, mentioned on page 7, there is an old picture showing Lutheran pastors conducting the Holy Communion; surplices with and without sleeves are worn by these clergymen. They also wear chasubles.)

P. S.—Just as I am writing this there comes to hand the February issue of the Synodical Bulletin of the Synod of the Northwest. In this there is a picture of two Lutheran clergymen, one in a sleeveless white surplice, the other in the Calvinistic black robe. A note beside the picture says: “ … This surplice, presented to the pastor by Holy Trinity Slovak-English Congregation, follows the custom of the Slovak Lutherans. Recent studies of church vestments are revealing that there is much historic warrant in Lutheran churches of all nationalities for the white vestment. Many eastern U. L. C. pastors use it. There is no doubt that its use is becoming more general…”

It was my good fortune to hear that doughty old champion of the Bible and its Christ, Dr. James Burrell, shortly after he had passed his eightieth milestone. He was still the beloved pastor of the Marble Collegiate Church. Not only was he robed, and his assistant pastors as well, but the elders and deacons of the church, who had special pews near the chancel, were also robed. This, I said to myself, is as it should be. The robes, or vestments, do not set the clergy apart, as if the minister is on a different plane from his people. In that sense I am, with our Church, “low church” in my views. I have admitted, and do admit laymen to speak from my pulpit. But I do ask that the deacon who assists at our Communion services, ordinarily be robed. These externals are used for the purpose that all things may be done decently and in order. Instinctively I, at least, feel that this is becoming and proper. It is not the man we exalt, but the office. And every time I robe to go before my people, there is a silent, and often an audible, prayer, that my person may not intervene between God and the humblest of my listeners. It is my impression that the shirt-sleeved exhorter impresses his own person and words far more upon the listener than does the preacher who is robed in the vestments of his church. The following word from the Altar Book of the Bishop of Lund, Frantz Wormordsen, “Handbook for the Proper Evangelic Mass” (Malmö 1539) may not be amiss:

Reverend J. Madsen, United Danish Church, wearing the ordinary black robe and white surplice. This is the historic and proper vestment for a Lutheran clergyman for all churchly services except the Holy Communion.

“The pastor and the Altar should be clothed with the usual vestments—clean and orderly—not for any service that we can render God by it, nor that there in any manner is any special holiness in it in regard to the use and effect of the Sacrament. But this shall be done as a good, proper and fitting custom—an honor—not to God but to the Christian congregation, and as a service of unity. So must everything in the Christian congregation be done honestly, decently, and in order—were it for nothing else than for the angels of God, who are there present among us.” Individual tastes in trousers or neckties, and peculiarities in attire should not be conspicuous in our Lutheran pulpits. It is my wish, and is no doubt that of many others, that there might be more uniformity in our clerical robes. It is sometimes difficult to tell what denominations are represented at our ordinations or church consecrations. Some wear the traditional Danish-Norwegian “gown” and “ruff” collar. Others leave off the collar. Some wear the robe of the college under-graduate, some a sort of modified Ox ford gown with closed front, some a robe with a short stole-like ornament, and others a regular academic robe, and a few the historic Lutheran vestments. Some robes are made of poplin, others of expensive silk. All this does not make for order or uniformity. At larger ordinations the candidate who wears the white surplice is the noticeable exception. With him who, because of inherited tradition or acquired opinion, will not wear a robe, I have no real disagreement. Of him I would only kindly ask the same tolerance for my tradition and opinion which I cordially grant to him. But I do plead for a larger effort at uniformity among us who wear robes. Please, let us get away from home-designed robes. They may be satisfactory to many of us, but there is already too much variety in our robes. ,

I desire further to ask: Why are we giving up o~ discarding the historic, and, as I believe them to be, really beautiful, Communion vestments of our Church? If we could agree upon wearing these, the entire problem could be solved easily and economically. There has been published, of late especially, some material concerning the proper Lutheran Communion vestments. The most readable and dependable with which I am acquainted is by a Danish clergyman, P. Severinsen. An abbreviated translation has been published by the Rev. J. Madsen, the rector of the Ebenezer Old People’s Home at Brush, Colorado.

(Joseph Braum: Die Liturgische Gewandung, Freiburg, 1907; Paul Graff: Geschichte der Auflösung der alten gottesdienstlichen Formen, Göttingen, 1921; A. Bugge & T. Kjelland: Alterskrud og Messeklær i Norge,” Oslo, 1919; Agnes Branting: Textilskrud i Svenska Kyrkar från ä1dre tid till 1900, Stockholm, 1920; P. Severinsen: De rette Messeklæder, Copenhagen, 1924.)

Suffice it here to state that the following are historically the traditional Lutheran Communion vestments: 1. The gown, or cassock. Popularly known as the “robe.” 2. The white surplice, or “cotta.” Historically known as the “alb.” This latter is, from ancient times, the robe of the Christian preacher. It is of linen. In olden times it was sometimes sleeveless. (See foot note, page 5.)

3. The “chasuble.” In Scandinavia it is known as “messehagel.” (Note the word “mass” in this connection. Luther’s order of services was built upon the old order of the mass. I shall elaborate this in a later article.)

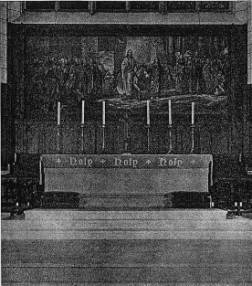

The beloved Bishop Laub of Denmark. The proper vestments for a Lutheran Bishop. The “ruff” or collar is peculiar to the Danes and Norwegians.

The black gown in use by the Danes and the Norwegians, for instance, was, 150 years or so ago, the ordinary dress of the clergyman in his daily life. The “ruff” collar has no ecclesiastical or churchly significance. It was the badge of the nobility, later of the king’s appointees. The Swedes and Germans do not seem to have worn the “ruff,” after feudal days.

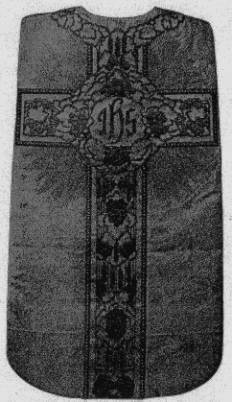

A beautiful Gothic chasuble, such as Worn in Reformation times. This One was made by the deaconesses of the Motherhouse in Stockholm, 1911.

This “gown,” the narrow-sleeved black robe of the Danes and the Norwegians, is, strictly speaking, not, when worn without the surplice, an ecclesiastical vestment. It was the pastor’s everyday dress, just as today many Protestant clergymen of all denominations wear a special garb, be it the high-cut vest, the Roman collar and rabat, or the white bow-tie and the “Prince Albert.” I am so naive as to believe that this old “gown,” when it is worn with the “ruff” collar, is a dignified, serviceable and proper robe, nevertheless. But for various reasons it will not come into general use among American Lutherans. In my opinion, it should be retained and used in the Norwegian and Danish-speaking churches. It has one advantage for him, however, who owns one and who finds it desirable to adopt another robe which is churchly and which will, I hope, eventually become the liturgical vestments of the American Lutheran Church. Let him procure a properly-made and fitted white surplice. Use this over the black robe, after having removed the black stole, and of course without the “ruff.” Let him, further, use a stole made for the purpose, one not over 48 inches long. (I like the 45 inch stole. This length is also standard among Anglicans. One maker of robes advertises a 48 inch stole as the “Lutheran stole”). The stole is one of the very oldest Christian symbols of the ordained clergy. (The clergy wore it over both shoulders, hanging down over the front of the surplice; the deacons wore it over one shoulder only.) And, let these stoles be made in the time-honored and sanctioned color symbolism of the Church. Thus, with the addition of a white surplice, which any dressmaker can make, and stoles which can be made as plain or elaborate as one, may choose, any clergyman possessing a black gown, is robed for his service in an American Lutheran church. But, at all events let him use the white surplice, even though he, for some reason or other, prefers not to use the stole.

At this point it may be worth noting that the beautiful old custom of changing the vestments (paramenta) on Altar and pulpit, with the church seasons, is coming into general use again. Lutheran church calendars are now published, which give the proper seasonal colors. Thus, during Advent and Lent, purple or violet is upon the Altar and pulpit. At Christmas, the Epiphany Sundays, and the Easter season, the church color is white. The Trinity season uses green. On Whit-Sunday, Reformation Sunday, church dedication day, memorial days, etc., the color is red. Some times black is used for funerals, Good Friday should have black Altar hangings. I recall that while at Luther College, a custom was observed in the First Lutheran Church of Decorah, which made a powerful impression upon me. During Holy Week and Good Fri day the beautiful “Good Shepherd” painting on the Altar was hidden by a frame covered with white cloth, upon which was a large black cross. Easter Sunday morning, the painting greeted us again with its silent but impressive sermon.

The so-called “Lutheran gown,” a black robe with a shirred back and closed front (sometimes worn with two white bands below the collar), is only about 150 years old. Its origin, tradition, and history is primarily Calvinistic. Because of the unfortunate decision after the Thirty Years’ War that the religion of the people should be that of the reigning house untold doctrinal and practical difficulties arose.

This is the chasuble so well known to the older generation of Danes and Norwegians.

I make a few quotations from Severinsen — Madsen’s ed. page 26 ff.:

“It was a Reformed king who declared war against the Communion vestments of his Lutheran subjects. The royal house of Brandenburg, Prussia, was Reformed while the population was largely Lutheran. The war against the Communion vestments was declared by the peculiar soldier-king Frederick Wilhelm I, who ruled in a very autocratic fashion. Through a decision of 1733 (Note the year) he prohibited copes, Communion vestments, candles, Latin song, chants, and the sign of the cross.”

There was much opposition. From a Lutheran plea to the king, printed in 1737, we quote:

“These things (i.e. vestments, etc.) are admittedly not any inner necessity but they have become no insignificant mark of our Church, and must therefore be safeguarded under these circumstances. The king gives the papist and the Jews full liberty of worship. Should then the Ev. Luth. Christians not be able to obtain the same protection and liberty?”

It is worth noting that the pietists, with their dread for externalism, did not, as a rule, support the royal command. “Some obeyed, but a number of places protested.”

Frederick the I was succeeded in 1740 by his son, Frederick the II, who rescinded his father’s injunction. But the years in which Lutheran usages had been prohibited, had their effect.

The time of Frederick the II was the time of rationalism. And rationalism completed what the Reformed king of Prussia had begun.

“Taken as a whole, the German Lutheran minister appears at the present time in the black Calvinistic cloak handed him by the Reformed king of Prussia. It should therefore be remembered that the Calvinistic ‘blackness’ of the clergy in the present day German Lutheran churches and her daughters, is not only not Lutheran—but is a remnant and constant reminder of a period of the greatest helplessness and degradation of the German Lutheran people. The brutal Prussian king followed by the overwhelming power of rationalism, did accomplish one thing as far as externals are concerned: It shifted the German branch of the Lutheran Church and her daughter churches (also here in U. S. A.) from her natural position among the great historic communions of Christendom—to a place among the sectarian Calvinistic denominations.

A Scandinavian Lutheran is still glad to say: ‘Receive the sign of the Holy Cross upon thy forehead and upon thy breast as a token that thou shalt believe in the crucified and risen Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ’.”

I might add, he is also glad to make the sign of the cross, concluding the Aaronitic Benediction, and at the dismissal following the Holy Communion.

“The original and typical apparel of the German Lutheran as of all Lutheran clergy when officiating in the sanctuary, is not that of ‘blackness and gloom,’ but the festive apparel of the historic church through the ages. We of Scandinavian ancestry cannot be too grateful for the better conditions prevailing in the mother countries.”

The story of the unfortunate changes in the vestments of the clergy, the use of the sign of the cross, candles, the color symbolism of the church, etc., wrought by rationalism particularly in Germany and to a lesser degree in Scandinavia, is too lengthy a chapter for this article. The reason rationalism did not succeed so well in removing the external tokens of Lutheranism in the Scandinavian countries, was this: their kings were Lutheran, at least in name.

Suffice to restate our premise: What Reformed kings had not finished, was completed by rationalism; and the historic church, which Luther wanted to name, “The Evangelical Christian Church,” became in its vestments and liturgy largely a copy of the Calvinistic sects.

Luther retained the Communion vestments which were considered an entirely neutral matter. In the order of the mass of 1523 Luther says that: “The vestments may unhindered be used when pomp and luxury be avoided, but they should not be dedicated or blest.” This position was, however, the very opposite of that of the fanatics who wanted to abolish all the ancient and historic vestments, liturgies, etc., etc. This placed Luther in the peculiar position, t.’ hat he was forced to emphasize liberty in these Matters by emphasizing the liberty to continue the use of the ancient Communion vestments. In the fall of 1524 he thus wrote:

Here we are masters and will not submit to any law, command, doctrine, or verdict. (Suppose Luther had been living in 1737!) Therefore has the service of the Communion been celebrated in both ways at Wittenberg. In the monastery we have celebrated the mass without chasubles, or elevation—with the greatest Simplicity as recommended by Karlstad. In the parish church we have chasubles)’albs, Altar, and elevate so long as it pleases us.”

In 1526 he retained the vestments, candles, and Altar. In 1528 he contended against fanatics again, and insisted on liberty to continue vestments, etc. In 1539 Luther said:

“When only the Word may be preached in its purity and the Sacraments rightly celebrated, then go in God’s name in procession and wear a silver or gold cross; wear a cope and surplice of silk or linen; and should your master, the duke, be not satisfied with one cope or surplice—put on three, as Aaron, the chief priest, did put on three, which were beautiful and glorious—wherefore the vestments in the days of the pope were ‘Ornamenta’—for such things (when otherwise no abuse takes place) neither add to nor take away from the Gospel.”

In the motion picture depicting the story of the English nurse, Edith Cavel, is a scene that made a deep impression upon the audience. The nurse is in the death cell awaiting her execution. The title on the screen announces the visit of “the Lutheran priest.” He comes in that conventional black robe, which several makers of robes catalog as “the Lutheran gown.” I have never like it. It makes no appeal to the eye. I could almost sympathize with the nurse, who asks for an “English priest.” A Church of England “priest” is then ushered into the cell. Over his arm he carries the neat surplice of the old Christian Church, and the colorful stole, the mark of the ordained clergyman. Shortly after, he appears vested, seated opposite the doomed nurse, facing her across the table. Then she makes that beautiful confession: “I have come to see that patriotism is not enough.” There is instinctively a catch in your throat and a mist before your eyes. And, as a Lutheran, I felt that in this contrast of vestments our faith was made to appear somber and joyless. No wonder an esthetic and refined soul longed for the simpler and more cheerful vestments of her church, than that black robe with its many shirrings and clumsy sleeves.

----

|

S |

OME few years ago I read an article in The Lutheran (U. L. C.) in which the writer, as I remember, expressed the hope that the historic, Christian and Lutheran, white surplice might come into general use again. I recall that he expressly stated that the Scandinavians continued the use of this churchly vestment, and he also mentioned some places in Germany where it was still in use. This question has also been debated, somewhat, in The Lutheran Witness (Mo. Synod). I may be prejudiced, but of course my verdict was entirely for the reverend gentleman who upheld the use of the white surplice as being traditionally “Lutheran.”

No, let us use the white surplice as a part of our ministerial robing. It was worn by Luther, Paul Gerhardt, Bugenhagen, Olavus Petri, Laub, Bang, Heuch, and our own immediate forbears.

The Rev. D. E. Snapp, 1860-1923. For 33 years the beloved pastor of the Martin Luther Church (Ohio Synod), Baltimore Md. This is the historic and correct vestments for a Lutheran clergyman.

Churchly, colorful, simple, neat, economical and practical!

To such as have not a gown, and who intend to procure one, I would say: a perfectly satisfactory and usable cassock, or black robe, can be bought readymade for from $12.00 to $50.00 (the cost depends upon the material). I have one which I have worn for more than eleven years; it cost me $18.00. Better still, any dressmaker can make one for you. There are pastors’ wives who would gladly have this work. Any seamstress can make the surplice. The drygoods stores which carry Butterick or other national patterns can procure the design. The women of my church have made about 160 cassocks, or robes, and equally as many white surplices for our two choirs. They have also made a stole and surplice for the pastor. The stoles are more expensive if bought ready-made. But far better, they can be made by the ladies and young women of the church. A pastor of the Ohio Synod writes me: “We have three sets of stoles in the seasonal colors, all made by women of the church. They have also made our chasubles.” The stole allows of individual expression in the embroidered symbols and designs.

The red “chasuble,” if I remember, was adopted in its final form as late as 1831. In Sweden and Den mark, and also in churches in America they are more and more returning to the more beautiful and ancient churchly chasubles in white, violet, and green.

The time has come, it seems to me, that we should express our faith also in our vestments and liturgies. Our Church is certainly sufficiently historic and sufficiently true to its ancient confessions, to have that privilege. I came near saying: it has the obligation of witnessing before the world that we are of the Lutheran Church. Some will say that I am pleading for the vestments of the Anglican Church. Well, should it be less proper that we wear robes like the founders of our own communion than that we wear those of more recent churches? And, as a Danish bishop said in England, not long ago: “Among us Lutherans it has caused no upheaval that we have continued to wear the vestments of the ancient Church. Among us it is not thought ‘Romish’ that our clergy wear the ‘chasuble’ at the Communion.”

In my opinion our greatest danger, doctrinally, does not lie through Rome, but through Geneva. The infiltration of Reformed theology through the increasing use of Reformed vestments, liturgies, and practices may not be noticeable today. But remember that externals are, after all, the outer form. And if the forms are the same, it will be inevitable that eventually some will become disposed to ask: Why cannot the contents be the same?

For me it was a perfectly natural thing to wear the white surplice. As a boy I had seen our pastors wear them. My forbears and my father used surplices. All who took part in my ordination had them. My seminary classmates had them. In my ministry, from the very beginning I wore one on all festival days of the church year. I always saw them at the ordinations and church dedications. The roomy surplices, so often worn by our older clergy, are a later invention. They had be large to be worn over the fur coats necessary in the cold churches of the Continent. In these days of steam-heated churches we can go back to the original form.

It is an easy matter to accommodate myself to the stole. My old gown had a black one. How much easier, however, I find it to wear the loose hanging, and sets the ordained clergyman apart from the choir if that wears the surplice. If worn in the beautiful seasonal colors (we have a remnant of this practice in all of our churches, where green or red is used on Altar and pulpit) it makes a fine appeal to a world hungry for color. I quote from Winfred E. Garrison in his book “Catholicism and the American Mind,” After he has enumerated a number of reasons why he believes the Roman Catholic Church has been able to maintain such loyalty among its members, as it admittedly has, he says:

“More potent than any single item in the above list, perhaps, is the appeal to color-starved moderns whose own lives are common-place but who yearn for pomp and pageantry. The mood of the romantic mediaevalist slumbers in the background of even prosaic and realistic souls, and sometimes it awakens to clamor for satisfaction. John Citizen has schooled himself to wear a gray suit of readymade clothes and a derby and to carry an umbrella, but there are certain cells of his brain that yearn for a Plumed hat, a jeweled sword-hilt and golden spurs. He lives behind rollershades of unobtrusive tint, but part of him longs for floating banners, yellow, glorious, golden, with splashes of crimson and dashes of blue. He loves his flat or his bungalow, but all of him cannot live there. He does not know it—though the people who build the newer motion-picture theatres know it—but he is starved for color, and something in him responds gratefully when it is offered to him either by a circus parade or by a cardinal’s procession.”

There is a wealth of good psychology expressed here!

In my estimation the surplice and stole worn over a plain and inexpensive black robe are far more in keeping with our Lutheran service, than an undergraduate or academic robe, no matter how the front is closed or how elaborate or expensive it may be. After all, it remains a black robe, more or less the badge of Calvinism and rationalism and certainly not historically, the traditional robe for an evangelical Lutheran pastor.

Further, what can be more practical and convenient than to have two or more surplices. One can always be kept neat and clean. And it is not as difficult to pack for travel a light-weight, plain cassock and a light surplice as it is to carry a more elaborate silk gown. Silk cracks and wears. The doctor’s robe which I have and use on academic occasions, and frequently at the informal, non-liturgical evening meetings, needs repairs more frequently than my cassock or surplice. These last, further, are used infinitely oftener.

The chasuble was also readily worn. The one I now use was presented to me by the president of our Church, Dr. J. A. Aasgaard. He had used it while pastor at Norway Grove. A former pastor of this congregation, the sainted President H. A. Preus, undoubtedly regularly used a chasuble at the Communion, as did so many of the fathers of our Church.

Of one thing I am convinced by experience, and that is, that “Young America” will love and revere the historic and colorful vestments of our beloved Church. There can be no doubt, but that vestments and church usages are partly responsible for the loyalty and faithfulness so frequently found among the members of denominations and churches which revere and respect their own traditions.

If possible I would like to prevent that any visitor at my services, departs with the impression that we Lutherans are one of the Reformed Church denominations. Particularly does this hold in reference to the Communion services. Though we are Protestants, we are a distinct communion with a doctrine, faith, hymnology, liturgy, and church practice all our own. We believe that historically and doctrinally we are the true heirs of the ancient Christian Church. Our own confession is the oldest denominational document of all, dating from 1530. The Roman Catholic confession, as adopted at Trent, dates from 1563.

Let us not be ashamed of, nor disinclined to confess in every way, the faith, usage, and practice of our fathers. Why should we American Lutherans be so influenced by the Calvinistic-rationalistic customs of the old countries, and the “kill-joy” usages of Puritanism, as to deny to ourselves and to our children the joy of beauty in color, music, and architecture? God certainly paints in glorious colors the works of nature, and the wonders of His creation are past finding out.

There is in American church life a decided reaction against the cold barrenness and dark legalism of the Puritan expression of Christianity. Now, when others are slowly but surely pulling themselves away from these influences let us gladly accept and use our own beautiful heritage. In my opinion it will also be one of the strong protections around that contained within, and presented through, the outer form, namely, our precious doctrines.

I have before me, as I write, a photograph taken at the consecration of an English Lutheran church, Ohio Synod, in Baltimore There are upward of twenty clergymen, all robed in the historic vestments. The congregation is so large that the service is held outside the church. Can you visualize the impression this service makes upon the hundreds thronging about for to see and to hear! The clergy are robed in plain black robes, i. e., cassocks, over which are the neat white surplices and the stoles. This day the stoles are red—for that is the color to be worn on such occasions. The choir is also robed with white surplices over black robes. Churchly, colorful, simple, neat, economical, practical—and not at all foreign or offensive to the native American eye, is this gathering of Lutheran Christians. And—better still, distinctive of our Church and its ancient doctrinal and traditional heritage. This service, by the vestments of the clergy, at once sets itself apart from any gathering of Reformed, or Puritan denominations. It is the historic heir of the ancient Church, thoroughly at home anywhere; speaking in any language; a part, even if a small part, of the Church universal of the ages.

-----

|

I |

N his admirable little compendium on Liturgics, Dr. Horn defines our problem thus

“What is meant by the Science’ of Liturgics?

Liturgics is that branch of theological science which treats first of the theory of Christian worship; and secondly, of its fixed forms.”

He thus defines that task of the Protestant liturgist:

“It is not the task of the Protestant student of Liturgics merely to discover the present order and traditional parts of Christian worship, that he may submit to them, nor has he to invent a service agreeable to the idea of Christian worship. He has simply to ascertain the service of the Church, which has been developed by its own inherent life, to try it by Holy Scripture and by, history, to correct it where necessary upon these principles, and, where the occasion demands, to serve its further development on principles accordant with its idea and in harmony with its past history.” (The italics are mine—J. A. O. S.)

A thorough-going study of the order of services in our Church would therefore acquaint one with the history, growth, and development of the Church. It would further discover the doctrinal content, and above all, the Scriptural warrant for so much of that which we have come to know as the Liturgy of the Church.

For after all, the Liturgy is the outward presentation of the faith of the Church. And, it must not be forgotten that through long centuries, the Liturgies of the Church were the only means of Grace, through which were kept alive the fires of faith kindled on that first Pentecost in Jerusalem. In spite of the accumulated debris of superstition; in spite of a growing tyranny exercised by a worldly-minded hierarchy; in spite of errors and falsehoods—nevertheless the Liturgy still retained much of the old truths once committed to the saints.

He must be a person of little imagination who, when leading a Christian congregation in public worship, is not himself profoundly moved. I think of him as standing before the Altar, which reminds us of the Lamb of God, that was for sinners slain. I think of him as leading the congregation in the confession of the age-old creeds, redolent with the memories of saints and martyrs. And as he lifts his voice to say: “I believe in the holy Christian Church, the Communion of Saints,” his heart is flooded with the vision that transcends all power of speech to describe. He is one of the long, long line of those chosen by the Church to lead the people in orderly, dignified, solemn, and continuous worship. He is, after all, the ambassador of God, who with the apostles of old calls his fellowmen to be reconciled with God. And—lest he be puffed up in his own conceits, he is reminded that of himself he is nothing. A thorough knowledge of his church liturgy would soon teach him that. But he does believe that God has called him through the action of that church which called him to be its pastor.

“The Liturgy should express the consensus of the Orthodox Church in all ages and places. And the Lutheran Liturgy will very properly emphasize the funda-

PAGES 21-24 ARE MISSING

her to Central Lutheran. She remembered nothing about hymns or music or sermon. But one thing had pierced her heart. She said: “You turned to the Altar and prayed for yourself and us, for the forgiveness of sins. Then you turned to us—and oh! it was as if you said it to me alone—‘he that believeth and is baptized shall be saved.’ I want to be saved—I want to be baptized—I want to be a Christian.” This young woman was baptized in the presence of a great congregation, on a Palm Sunday. At last reports, she was living true to her baptismal vow. A liturgical Christmas service at midnight was the conversion of a stalwart athlete once captain of a championship university football team. Also he asked for, and received, Christian Baptism at a public service.

And why should it not be thus? Are the more or less spontaneous prayers of to-day, more spirit-filled, more inclusive, more true to experience, more in keeping with the Gospel than, for instance the old confessions, the old collects, and the prayers of the Church of the ages?

Are the applications we present-day speakers make of the Law more searching, more convincing of the self-satisfied conscience of to-day than the piercing words of the old confession?

Are the Gospel declarations we make in our sermons more comforting than the solemn Words of Christ as embedded in the chaste ornamentation of the old absolutions?

Merely to ask such questions is to answer them, it seems to me.

-----

|

T |

HERE are some books which should be in every Lutheran pastor’s library. I mention some that I consider not only helpful, but elemental:

1. Outlines of Liturgics, by Edward T, Horn. The second edition, neatly bound, consists of 165 pages. Its eleven pages of bibliography are invaluable for him who would study further. Young pastors and students should memorize parts of it. This is a classic. it is entirely dependable. I have compared many of its quotations and conclusions. If the pastor can have one book on Liturgics, by all means let him procure the above book.

2. Christian Art, P. E. Kretzmann. This is a very comprehensive volume of about 450 pages. Anyone with a spark of reverence for his church; anyone who desires to feet himself in touch with the saints of old, will thrill at the reading of it. It covers the whole range: Church Architecture, Symbolism in buildings and appointments, the History of Liturgy from the Old Testament times to the Reformed Churches of U. S. A.; Hymnology is discussed in five interesting chapters; six chapters are devoted to the Church year; and six chapters discuss the Liturgical Contents of the Lutheran Services. Even the different synods and the characteristic marks of their Liturgies are briefly illustrated. This excellent volume, also for sale at Augsburg Publishing House, net $3.50, should be in every pastor’s and teacher’s library. Sunday School and Y. P. L. libraries should have it. Of course it cannot be expected that everyone will agree with all of Dr. Kretzmann’s conclusions. That would be expecting too much from a volume that covers such a wealth of subjects. His chapters on “Symbolism” do not satisfy me. Some of his conclusions and assertions in the matter of church buildings, etc., are at times neither correct nor in keeping with the high idealism for which the author is such an able exponent. He cannot have had available very much material of value touching the interesting matter of vestments. Some of the illustrations of Lutheran church buildings prompt me to ask: Are these here in order to show us how not to do it? But I desire to say, nevertheless, I have read this book with intense delight. Parts of it I have reread, and expect to read again. And—1 have read considerable on all these matters. (By the way, Mr. Thomas J. Gaytee is now writing some interesting and reliable articles on Christian Symbolism in Glass, for our Lutheran Church Herald, the Y. P. L. edition.) I feel satisfied that the premises, development, and conclusions, and suggestions of Dr. Kretzmann’s book, on Liturgical Matters, are historically, doctrinally, and traditionally correct.

3. Then there is a readable and very interesting little book entitled: The Explanation of the Common Service. This also has appendices on Hymnody, the Liturgical Colors, and a valuable glossary of Liturgical Terms. Augsburg Publishing House also has this in stock.

4. Another valuable book is Dr. C. H. L. Schuette’s Before the Altar. This production consists in a “Series of Annotated Propositions.” It is done in the good old style of the dogmatician. The Lutheran student will find it packed with logic, history and doctrine.

-----

The earliest Christian worship was, it seems twofold nature. There were two sorts of assemblies, one in the Temple, the other “from house to house.” In the first of these they exercised their calling as missionaries. Thus, the first Christian sermon which Peter delivered from the flat roof of that building in Jerusalem; thus the first sermon and missionary work of Paul.

The early Christians went to the temple as Jewish Christians. Their release from the observances of the Jewish religion was gradual. It was probably not entirely consummated until after he destruction of the temple.

The early Christian worship described in Acts 2:46—“and breaking bread from house to house, etc.”, was the distinctly Christian worship of the first Christians. No Liturgy was prescribed by divine law or by the apostles. But gradually there was developed out of the first practice, the complete Liturgy of worship.

After a short time the Christians were excluded from the synagogues, and their gatherings were held in the houses. Also among the Gentile Christians two sorts of assemblies seem to have been in use from the very beginning. The public meeting, and the meeting “from house to house.” The public meetings were invariably of a missionary character. The chief element was, naturally that of instruction. There were lessons from the Scriptures, and addresses. There were various “gifts,” speaking with tongues, prophecy and teaching. Paul, the great missionary, reckons “teaching as the highest gift (I Cor. 14:19). In it began the later churchly “homily.” Prayers and songs also formed a part of these services. The private assemblies consisted of reading and teaching the Word of God; of Psalms and hymns and spiritual songs; of supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks; of offerings or the common benefit, all culminating in the Lord’s Supper, with “the holy kiss,” and with the “agapes” or love-feasts These love-feasts soon were abused and fell into decay (I Cor. 11:20-22).

From this point on, historical material becomes increasingly available.

From Dr. Schuette I shall adduce some forms of worship in the ancient Church. He says: “So far as can be ascertained from the writings of the Fathers the worship of the Church as far back as the end of the third century—if not further—proceeded as follows:

A) The Mass of the Catechumens (or learners)

1. Private Confession.

2. Singing of the Psalms, beginning with the sixty-third, and ending with Gloria Patri.

3. The Pax (Peace be with you) with response, thereupon reading of the Scriptures from

a) The Law,

b) The Prophets,

c) The Epistles,

4. Singing of a Psalm.

5. Reading from the Gospel, closing with Deo Gratias (We thank Thee, O God) or, Laus tibi Christe (We praise Thee, O Christ) by the congregation.

6. The sermon, beginning with the salutation: “The grace of our Lord, etc.”, or “Peace be with you.”

(Following the sermon, all unbelievers were dismissed.)

Thereupon followed the prayers of, or in behalf of, 1, the Catechumens; 2, the Energumens; 3, the Photizomens; and 4, the Penitents. Each class was dismissed at the conclusion of the intercession made in its behalf.

B) The Mass of the Fidelium, i. e., the faithful or believers.

1. All (believers only now being present) are admonished to private devotion.

2. The General Prayer—every separate petition being responded to by the congregation with, “Lord, have mercy.pl

3. The Collect.

4. The Offertorium, or collection of gifts.

5. The Preface: The salutation with response; the Sursum Corda, with response (We lift our hearts, etc.); prayer by the minister, with the Sanctus sung by the congregation.

6. The Consecration.

7. A General Prayer of Intercession.

8. A Prayer (referring to offerings made.)

9. Confession of Faith (Since A. D. 471.)

10. Probably the Lord’s Prayer—certainly post-Nicene.

11. The Holy Communion (with singing of Thirty-fourth Psalm.)

12. The Post Cornrnunion with Prayer of Thanksgiving, Benediction and “Go in peace.”

“Preach the Gospel”

Thus it will have been noted that the Liturgy, in spite of the fact that it was still in the process of development had, by the end of the third century “assumed the general form which it later had in all great Liturgies, that is, with two important parts, (1) a preparatory service, called the “Service of the Word,” and (2) the main service. Certainly only a little later “the Mass of the Faithful” is very complete. Little by little “the teaching of the Church became corrupted, and the worship of the Church naturally showed that corruption. Men were taught that their works and prayers, their pilgrimages and fasts atoned for their sins. Christ’s work of atonement, and faith in Him, were lost to sight. This inevitably led to the perversion of the sacramental element of worship, and the undue exaltation of the priesthood; and the whole service even to the Lord’s Supper came to be regarded as a sacrifice offered to God by the priest on behalf of the people. This was the fundamental error of the Romish Church of the Middle Ages.” (P. 11 ff., Expl. of Common Service.)

But, as always when the cup of iniquity is full to overflowing, God remembered His people and His covenant with them. The Lutheran reformers led the way. The Twenty-fourth Article, for instance, of the Augsburg Confession indicates definitely the ideals of the “Conservative Reformation.” “It was a Reformation, and not a revolution.”

“Luther had no intention of tearing down and destroying without regard to history and custom, but aimed to edify and build up. He insisted upon correcting the abuses which were based upon false doctrine. . Whenever there was a reason for retaining a good ceremony, or one which was not in itself sinful or dangerous, Luther gave his reasons. He did not, for instance, like the word ‘mass’—to him it savored of Romanism and false doctrine. He preferred the designation, ‘Communion’. In spite of this he retained the word ‘missa,’ thus signifying that in the external form of service he did not wish to establish anything new, but merely had the intention of leading back to old, correct form of worship.” … “Thus the reformers worked with all energy at the gigantic task.” (i. e., cleansing the old order of Christian worship from every vestige of false doctrine and human superstition, and still maintaining unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles, Saints and martyrs.) They produced scores of service books which were free from Roman doctrine and superstition, and gave the people an opportunity to take an intelligent part in services, which were for the most part conducted in the vernacular. Luther had good reason for writing, in 1533: ‘God be praised, in our churches we can show a Christian, a right Christian mass according to the order and institution of Christ, and according to the true meaning of Christ and the Church. There our pastor, bishop, or servant in the ministry, correctly and truly, and openly called, who was consecrated, anointed, and born to be a priest of Christ in Baptism, steps before the Altar; he sings publicly and plainly the order of Christ, instituted in the Lord’s Supper, takes bread and wine, gives thanks, distributes and gives it by the power of the word of Christ: this is my body, this is my blood, this do, etc., to us who are there and wish to receive them have especially those intending to Partake of the Sacrament, kneel down beside, behind, and around him, man, woman, young, old, master, servant, mistress, maid, parents, children, as the Lord brings us together there, all true, holy co-priests, sanctified through the blood of Christ, and anointed and consecrated through the Holy Ghost in Baptism … that is our Mass and the right Mass, of which we no longer are in want.”

“Even Thine Altars, O Lord.”

(The above from Luther’s Winkelmesse und Pfaffenweithe, is quoted from Kretzmann, p. 282 ff.).

Luther is right. The old Christian Order as found in the “Saxon Lutheran” type of Kirchenordnungen, i. e., “order of Church Service,” is truly the historic service of the Christian Church down through the centuries. The multitude of Lutheran “Kirchenordnungen”, may roughly be divided into three classes:

1. Those which, while pure in doctrine, were almost too conservative with reference to their dealing with traditional forms.

“For a day in Thy Courts is better than a thousand.”

2. The Saxon-Lutheran type.

3. The more radical orders, which try to take a mediating position between the Lutheran and the Reformed types. (See Horn, p. 123 ff.)

Once in a while we hear someone say: The more liturgical Lutheran church services remember those of the Episcopal Church. Please note this reply; “The Lutheran revision of the service, issued in many editions, in many states and cities, had been fully tested by more than twenty years of continuous use before the revision made by the English Church, first issued in the Prayer Book of Edward VI., 1549. The Latin Missals, from which the English translations were made, agreed almost entirely with the Missals from which the German translation had been made.” (See Expl. Of Common Service, p. 13 ff.) English students of the Anglican Liturgies have stated that the prayer Book of James VI. has not been improved upon. That Prayer Book resembles the Lutheran orders, much more than the later orders of he Anglican Church. (See Kretzmann, p. 290 ff.; also Horn, p. 128 ff.)

The beautiful orders of the Saxon-Lutheran type maintained themselves until the Thirty-Years’ War. That fearful and protracted calamity very nearly destroyed all church order. After the close of it, nearly all the churches republished their church books (about 1650 and later). Through three periods of difficulty, (1) the period of orthodoxy (the growing emphasis on scholastic and dogmatic definitions), (2) the pietistic period (the emphasis on subjective, personal experience and gradual lack of emphasis of objective truth), (3) the period of rationalism (the greatest scourge that visited the Church—the rejection of the supernatural), there was a marked deterioration in every phase and form of church life. By the beginning of the nineteenth century the destruction was complete. Not till quite late in the last century (about 1877) did Germany obtain a “Kirchenordnung” in keeping with her glorious past.

It is certainly worth noting that not until about 1877 did Germany again have a pure Lutheran Liturgy; the new Liturgy of the state church of Sweden (1894) supplies the ancient Gregorian melodies for every part of the Liturgy; the Liturgy of the state church of Norway from 1920, comes nearer the original Liturgies than any since the days before rationalism; and it was in 1888 that American received her Common Lutheran Liturgy.

Thus it will be seen that we can all of us be along and make history, both in the matter of Liturgies and vestments. And the above facts should also encourage us as we note the definite and decided swing, all along the line, back to the old, pure Liturgies of the ancient Christian Church. I can only say: I wish that the “swing” back to the beautiful and colorful vestments of the old Church were as noticeable.

The Liturgies in the Lutheran Church in America

Naturally the Liturgies of the dozen and a half Lutheran synods of American reflect more or less their historic origin. The Church is naturally conservative. It is the last to change its order

But among English-speaking Lutherans there has been established a point of contact that, in the far-reaching promise it holds out, certainly seems providential. I refer to the so-called “Common Service.”

This historic old service of the universal Church appeared in 1888. It was compiled by a joint committee appointed by the General Synod, the General Council, and the United Synod in the South.” These three church bodies, and their constituent synods, had for years been editing and publishing Englished Liturgies for American Lutheran congregations. It must have been the Lord of the Church who brought about this joint effort on the part of these three Lutheran groups, who had been longest on American soil. A definite principle was set up to govern the work of this committee. It desired to present to the American Lutheran Church a Liturgy that represented the order of services which had the common consent of the pure Lutheran Liturgies of the sixteenth century. The year of 1888, and the church season, Whitsuntide, of that year, should always be gratefully remembered by American Lutherans. For that Year gave to our Church and the American people, not only a most beautiful, and traditionally correct, Lutheran Liturgy, but it gave to us for all times the most Scriptural and evangelical Christian Liturgy which has been possessed and used by any church denomination.

To-day that glorious Liturgy is in official use by the larger Lutheran church bodies, and probably also by the smaller groups. The United Lutheran Church in American, and its forty-five constituent synods have long ago adopted it. The Missouri Synod makes it the first order of services in its new agenda. The Joint Synod of Ohio uses it. The Norwegian Lutheran Church places it second in its English Hymnal; so does the Augustana. Synod. The recent Service Book of the Lutheran Church, issued by the United Lutheran Church, represents the high-water mark of liturgical publications by American Lutherans.

But let me again emphasize the universal use of this glorious Christian Liturgy. At least outwardly American Lutherans have a common order of worship. If we could only be half as consistent in our use of vestments! That is, if we are to wear liturgical vestments at all.

In a general way, it may be said that this service is made up of three parts.

I. There is the Preparation, or Confession of Sins. This is not always a part of the old services. But, if the Communion is not celebrated, it should no doubt be used because of its thorough Scriptural and evangelical content. (This confession is found on page 21 at the front of The Hymnary.)

II. The office of the Word, beginning with the Introit and ending with a hymn. (Of course, if there is no Communion, the Benediction must follow here.)

In general it may be said that these first two parts are what is presented in our American Lutheran churches on the average Sunday.

III. The Holy Supper. This properly begins with the Salutation and ends with the Benediction.

Practically every Lutheran liturgist insists that the Lutheran service always presupposes the Communion. Some even suggest that the service is mutilated if the Communion is not observed.

Now let us look at this a moment.

The early Church had a double service—or shall we say, it had a Liturgy for Sunday services which logically could be divided and which was divided into parts, A and B. It is more than a coincidence, it seems to me, that Schuette, on page 139, where be gives an outline of the earliest orders and actually quotes six different Lutheran orders, also divides that early Lutheran Liturgy into parts A and B. Thus Part A begins with the Introit and ends with the Sermon and General Prayer. Part B begins with the “Praefatio” (for Holy Communion) and ends with the Benediction.

Let us go back to the very beginning. The Apostolic Church (that of the first decades after the resurrection) also had two kinds of services: A. the Missionary, i. e., the teaching services for the learner and others. B. the “House to House” meetings, later named “The Missa Fidelium” (“The Mass for the Believers,”—when others were dismissed.)

For present day conditions there is much in this ancient usage which commends itself to me. The Lutheran order of service also adapts itself easily, beautifully, to this usage.

Now, let it be said that the Lord’s Supper should be observed far more frequently in Lutheran churches than is often the custom. The ideal should be that the Communion is celebrated every Sunday. But two practical questions arise:

1. Will not the services become too lengthy if the Communion is to be preceded by a typical Lutheran sermon of thirty minutes of so?

2. Will the Communion service convey the proper impression to those who are unacquainted with the old Scripture teaching? Should not the attendance at the Communion service be limited to those who, even though they do not communicate, at least reverentially remain through the entire solemn service?

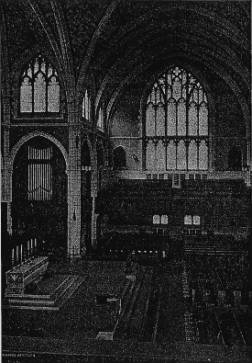

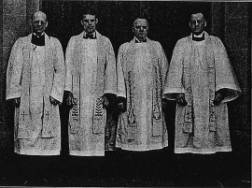

The Reverends: L. P. Bjerre, Arnold Flaten, J. A. O. Stub and H. O. Shurson, robed in Vestments worn at Communion Services in Central Lutheran.

I have noticed that it is becoming more general to hold special services for the Communion, also among Lutherans. Thus there are Lutheran churches where Communion is observed at least twice a month throughout the year. These services are held, some of them earlier, and others later in the day. Why not celebrate the Holy Communion every Sunday, say at eight or nine o’clock A. M.? Why not also have frequent evening Communions, say at seven-thirty or nine o’clock? At these (Holy Communion services) one should use the entire Communion Liturgy, beginning with the Salutation and Prefatory Sentences. (I always like a quiet organ prelude on some typical Lutheran Communion hymn. I also ask for a suitable short hymn to introduce the Communion Service. Of course no Lutheran pastor will celebrate Communion without having preceded it with a proper “Preparatory Service.” If the Communion is held at stated hours, as suggested above, there will also be time for a brief but certainly blessed “Preparatory Service.”)

It is quite comforting to me that Gustav Jensen, that fine liturgist and orthodox, pious Christian preacher of. Norway, seems to have come to somewhat the same conclusion, in this respect. He believes that we may conduct two types of services on the ordinary Sundays. First, the missionary, teaching service. Second, the Lutheran Communion service. And, I venture, that this is what we are doing anyhow! I do not know of a Lutheran church in America where the 10:30 or 11 o’clock service is always conducted with the observance of the Communion. Why not let us agree that it is in keeping with the Scriptures and the most ancient usage of the Church to have two kinds of services on the Lord’s Day?

Further, the beautiful Lutheran orders for vespers cannot always be used for evenings. Most Lutheran liturgists, both here and in Europe, usually presuppose a congregation (the hearers) composed almost entirely of such as are at least nominal members of the Lutheran Church. Such suppositions are not applicable in our American cities, even of the smaller size. Increasingly a large proportion of our hearers are not only non-Lutherans, but are not church people at all. Let us make our evening services frankly more evangelistic. Personally, I almost envy the Lutheran pastor who is so situated that at five or six or seven o’clock of a Sunday evening he can have a choir and congregation willing to meet up for the beautiful vesper service. But—most of us will have to remember that our business is to preach the Gospel; often to such as may hear us only once. Further, these mixed congregations cannot be expected to be able to conduct a Lutheran service. But, wherever possible at all, the chief service should always be according to the Lutheran Liturgy. It goes without saying that the Communion, to the last detail, should follow the tradition of our Church.

The Surpliced Junior Choir of Central Lutheran. The women of the church have made cassocks and surplices for both choirs.

The Surpliced “Senior Choir.” Note how the White Surplices add color and warmth.

In addition to the Sunday evening services (where these are held), the Lutheran Church must also give opportunity for other types of meetings. Liturgically-minded, though I believe I am, I certainly sense that there must be room for self-expression at prayer and Bible study meetings. Kretzmann says: “Acting upon the suggestion of Spener (one of the saner leaders of the Pietistic Movement), the public meetings of the congregation, public Communion and private confession were supplemented by private religious meetings in the home, private Communion and private conversation in the pastor’s study. But the revival of spiritual life, for which the early Pietism had hoped, soon brought about methods and caused sentiments which were destructive of the cultus of the Church. … A critical attitude toward the content of the sermon became evident; it was stated that the truth of the preacher’s discourse depended upon whether he were truly regenerated. The public sermon was no longer regarded as the most essential part of the minister’s work, but rather the individual pastoral cura. The idea of fixed parts in the Liturgy became increasingly distasteful to the Pietist.” (See Kretzrnann, p. 285 ff.)

Lutheran Vestments

Now, this is a dark picture. And Pietism is certainly not dead, by any means. But there is such a things a “balanced ration” also in Spiritual matters. A liturgical service, properly carried out by properly vested minister and choir will stand the test to-day. Personally I do not think our danger comes so much from the leaven of Pietism, as from that type of orthodoxy which may become and outward form. It may have the truth, it may speak with the tongues of angels, but it has not love. But it cannot be thought possible that anyone to-day will recommend private Communion, except as emergencies among the sick and shut ins. One fatal weakness of Pietism was its lack of appreciation of that larger and important question: What is the Church? Of course in its final analysis the Church consists only of the host of the saved, i. e., the Communion of Saints. In this sense, time, space, race, language or creed, all disappear, and only saving faith in Jesus Christ remains as a condition for membership in the Church of God. For want of a better definition, we have spoken of “the invisible Church.” But it must not be forgotten that the Church also has an outward “visible” existence. There has therefore been an organism which we call the Church. God has always had His Church, also upon earth. But this Church has never been free from imperfections and blemishes. There never was, and there never will be a wholly perfect and spotless church upon earth until Christ shall come to claim His bride. That little church of which the Lord Himself was the leader had a Judas, a Peter, a Thomas; yes, it had a group of whom it is said: “Then forsook all the disciples Jesus, and fled.” And nevertheless, within this group was the slender. bond uniting God to His Church on earth. Let us teach our people to love and revere the Church. And we ourselves must show the way by a reverent regard for the Church and its cultus. But we must also remember never to quench the Spirit. God can cause even the very stones to speak.

The liturgical chief service on a Sunday morning, is first of all for the purpose of glorifying God and edifying the Christian congregation. It also emphasizes our unbroken continuity with the Church of the Apostles and our Lord. As it also is “the service of the Word,” the evangelical pastor will so conduct every part of it; will so couch his prayer, and so deliver his sermon, as if it might be his only opportunity to reach some of his hearers, and his last opportunity of leading his own congregation in Christian worship.

*

Some things should, perhaps, also be said about the musical settings for the Common Service. The settings found, for instance in The Hymnary (p. 21 ff.) are practically the same as those published in 1888. Missouri also still uses them. The United Lutheran Church is making a laudable effort to get back to the old “plain song” chants. These are wonderfully impressive, but require an excellent choir and a trained congregation. (See Reed and Archer: Choral Song, Phila.; also The Book of Common Service.) Personally I have come to love the music of the Liturgy as we have it in our Hymnary. There must be some room for individual likes in the musical settings, just as there is in the symbolisms in our churches, the embroideries on our Altars, pulpits, and stoles. Some day there will be one Lutheran Church in America. I take it for granted that there is not one of us but constantly prays that God may bring this to pass. Let us rejoice, take hope, and thank God for every evidence of an increasing unity of faith, spirit, and purpose on the part of the Lutheran Church, both here and in Europe.

The American Lutherans, largely of German extraction, have preserved for us, and have acclimated for us, the wonderful Liturgy of the Universal Christian Church. Perhaps, under God, the American Lutherans, largely of Scandinavian extraction, shall bring as their contribution the hallowed and beautiful vestments of the same Church Universal of the ages. What a glorious heritage we have!

Of course a great deal more could be said. I have not, in this paper explained “the parts,” for instance, of the Common Service. What is the “Introit”? What is, and whence is, the marvelous “Gloria Deo in Excelsis”? We have left entirely untouched the occasional services and the different liturgical acts for which the various synods have their forms and agendas. The Communion Service, from the Praefatio to the Benediction, should also be discussed. The order of service for the Baptismal Ritual should be explained and illustrated. And something should also be said about the manner in which pastor, choir, and congregation deport themselves during the hour of worship.

I desire to close with some words from Kretzmann, p. 395 ff.: “Divine worship in the Christian, Church is not an adiaphoron. To argue that it is a matter of complete indifference as to how the form of Christian worship is constituted, would be bringing liberty dangerously near to license … It cannot be a matter of indifference to a Christian congregation when the order of service used in her midst shows so much similarity to a heterodox order as to confuse visitors … and a Lutheran congregation cannot justly divorce herself either from the doctrinal or the historical side of her Church. (Italics and slight change of wording by J. A. O. S.) … In addition to these facts, there is the further consideration that the outward acts of the Church, commonly known as the Liturgy, have a significance which in many cases renders the acts of public service true acts of confession of faith.”

An Outline of the Lutheran Liturgy

The Common Service may appear somewhat complicated and also difficult of execution for him who is not very familiar with it. Perhaps the following diagram may be of some help in analyzing and explaining the Common Service.

[We have reformatted this as an outline.]

Order of The Service or The Communion

I. The Preparation or Confession of Sins

Invocation—“In the name of the Father etc.”

Exhortation—“Beloved in the Lord etc.”

Versicle—”Our help is in the Name of the Lord etc.”

Confession—“Almighty God … we poor sinners etc.”

Prayer for Grace—“O most merciful God.”

Declaration of Grace—“Almighty God hath had mercy etc.”

II. The Service Proper

A. Office of the Word

1. Psalmody

Introit and Gloria

Kyrie—“Lord have mercy

Gloria in Excelsis

2. Word

Salutation and Response

Collect

Epistle

Hallelujah or Hymn

Gospel

Creed

Sermon, Hymn, Votum “The peace of God etc.”

3. Offering

Offertory—“Create in me a clean heart”

Gifts—“We give Thee but Thine own”

General Prayer

Hymn

(The Benediction and Amen)

B. The Holy Supper

1. Preface

Salutation

Prefatory Sentences

Eucharistic Prayer

Sanctus

2. Administration

Lord’s Prayer

Words of Institution

Pax

Agnus Dei

Distribution

Blessing

3. Post Communion

Nunc Dimittis

Thanksgiving

Benediction

The three parts (A 1-3) form the Missionary Service of the early church. Part I “The Preparation” is a later addition; it should always be used where there is no “communion.”

The three parts (B 1-3) form the “Missa Fidelium” of the early church. Preceded by a “Preparatory” Service is complete in itself.